Narrow Societies Create Strong Early-Stage Funds

The Structural Advantage Global Investors Are Missing in Korea

There’s a saying:

iron sharpens iron.

I think the same logic applies to startup ecosystems. Narrow societies are often criticized for being boring, yet they are also where some of the strongest early-stage investors and funds are born.

Why?

Because at the pre-seed and seed stage, investing is mostly about one thing: recognizing patterns and signals of great founders. That’s probably 90% of the job.

And in narrow ecosystems, investors and talented people are inevitably exposed to each other over long periods of time. Whether intentionally or not, they become trained at recognizing these signals.

Silicon Valley is the clearest example.

On the surface, the Valley feels radically open. Anyone from anywhere can move there. But in practice, it is also one of the most closed and narrow societies in the world. Like, it feels like a different world than the outside.

Stanford, Berkeley, and a handful of other institutions produce tightly networked talent. People are only one or two degrees apart. Programs like Y Combinator accelerate this density even further. Over time, strong founders, operators, and investors begin to recognize each other’s patterns. Reputation compounds. Signals accumulate.

Who did you work with? Who vouches for you? What have you built? How do you think?

These signals don’t emerge overnight. They form slowly, across decades of repeated interactions inside a dense network.

That density is precisely why Silicon Valley became the most active early-stage market in the world, where first-check angels thrive, emerging funds scale quickly, and new investors seem to appear every single day.

Now here’s the controversial thought:

I believe Korea shares more of these structural characteristics than global investors tend to recognize.

Not that Korea and Silicon Valley are the same. But structurally, Korea satisfies two important conditions:

high talent density, with globally competitive but still underpriced talent

a narrow network where signaling can compound efficiently

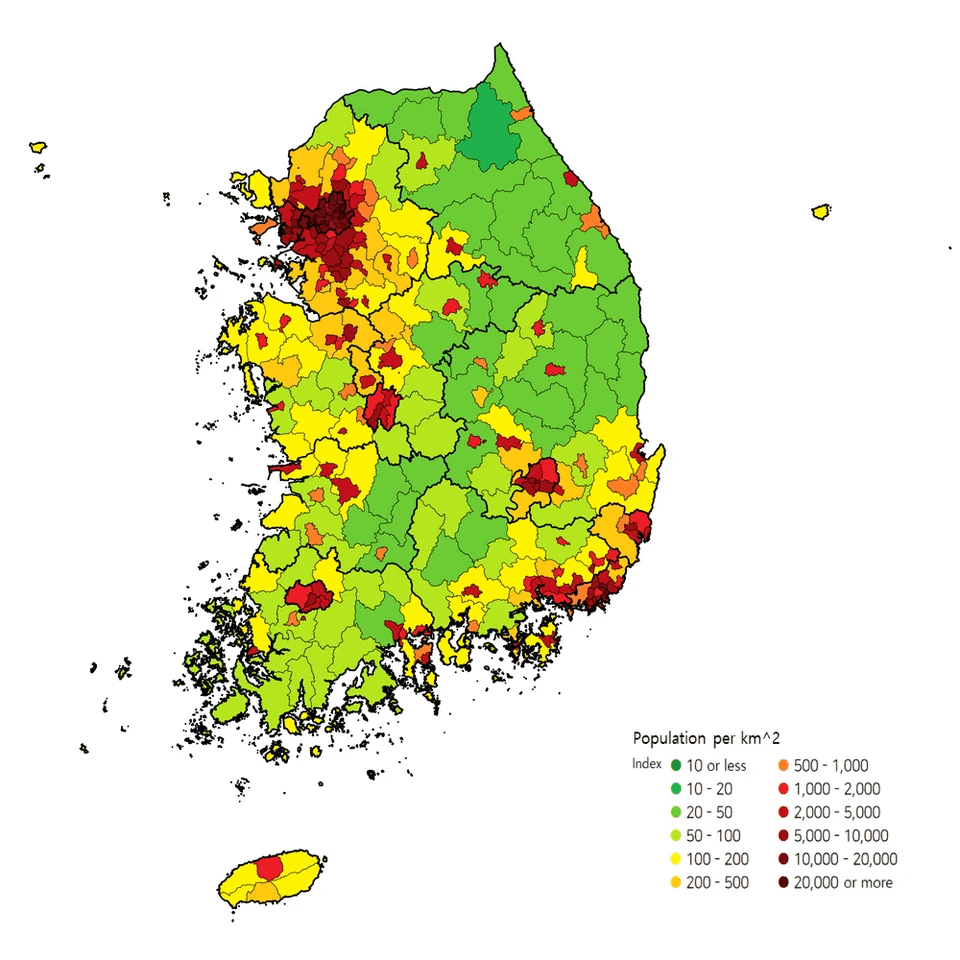

Korea is, for better or worse, an extremely centralized country. Roughly half of the population lives in the Seoul metropolitan area. Nearly all major companies, universities, and institutions are concentrated there. Practically speaking, most of the country’s top engineers, founders, and ambitious talent coexist within a single city.

This isn’t just geographic. It’s social.

Unlike the U.S., where there are dozens of elite universities, Korea has a much narrower funnel. Academic pedigree does not cause startup success, but the pattern is there. Many successful founders come from overlapping educational backgrounds: SKY (Seoul, Korea, Yonsei) universities, KAIST, POSTECH, and a few others. The ecosystem itself is small. The number of participants is small.

As a result, founders, VCs, ex-founders, and emerging talent are often already connected through school, previous companies, labs, clubs, student organizations, military service, or overlapping career paths.

In every generation and school year, the talented ones usually know each other, or they’re only a couple of LinkedIn connections away.

An ambitious engineering student at KAIST might meet a standout designer from Hongik while interning at Toss.

A founder who started building seriously around 2022 often knows who the sharp operators were in their peer group.

These networks form organically and tend to persist.

What matters is that this is not just a dense network, but a network of increasingly strong founders. Over the past few years, many Korean founders have been pushed by structural conditions to become more ambitious by default. The domestic market is small, competition is intense, and it is difficult to build meaningful companies without either thinking globally from day 1 or identifying unusually sharp opportunities inside Korea.

You see founders building global consumer brands in categories like beauty, content, and IP, where Korea has genuine strengths. You also see founders identifying structurally unique opportunities inside Korea, like how Coupang was able to make next-day delivery viable precisely because Seoul is so dense and highly connected. On top of that, the overall baseline of technical and analytical talent in Korea remains extremely high.

Taken together, this creates something rare: an ecosystem where investors can observe the same pool of high-quality founders over long periods of time, across multiple contexts.

Korea, and Seoul in particular, concentrates founder talent that is comparable to top ecosystems globally, while its narrow and highly interconnected network makes those founders unusually visible and legible to early-stage investors.

This is the structural advantage global investors often underestimate when they dismiss Korea as “too small” or “non-strategic” compared to India or China.

Narrower, smaller societies give birth to stronger early-stage funds.